|

Building the Canal in Shelby County

Work had begun on the flat stretches of land

here by the mid-1830s, before the canal was opened to Piqua in July, 1837. Local

contractors bid on the work by sections. Teams of oxen and mules provided the power to

haul away the material and deliver stone. The laborers worked with wooden scoops, shovels,

and wheelbarrows. J. W. Akin of Houston was awarded a contract for one mile of the

canal in Shelby County. J. W. Schworer and B. Ortman of Minster also were awarded sections

of work. Although the minimum top width of the canal was specified to be 40 feet, the

canal in this county averaged 45 feet wide.

Shelby County, Ohio, was covered by virgin

forests during this time. The canal builders often encountered trees with a diameter of

seven feet or more. These giants had to be cut down, and the stumps removed by hand. The men lived near the work site

in shanty towns where unsanitary conditions and disease were common. Working conditions

were miserable during much of the year, with freezing temperatures in the winter and the

threat of malaria (known by the canalers as 'auge'), cholera, and other diseases in the

summer. These problems were especially prevalent in Shelby County because of its swampy conditions. Terry Wright has written that,

for each mile of the canal, at least one worker died of sickness or winter exposure.

Fort Loramie historian Clarence Raterman recorded in 1940 the experiences of Henry

Meyer working on the canal, as related by his grandson, Richard Thaman. Meyer was a

contractor on the canal. He had to feed and board his crew, so he took his wife along to

cook for the men. The son of an area family, Henry Berning, worked for Meyer as a water

boy. Meyer later recalled that after his men had dug out the canal bed, clay was applied,

and cattle were driven down the canal to seal the bed. Meyer was quoted as saying, "I

never asked any man to do something I could not do. My work was the measure of what I

expected from my men. When I rested, they rested."

Meyer went to Piqua every two weeks with a cart to pick up supplies. On one occasion,

he was attacked by a pack of wolves, and he escaped by climbing a tree. He stayed there

until the next morning, when workers from his camp drove off the wolves. On another day,

Meyer looked up in a tree beneath which he was passing, and saw a large snake coiled on a

tree branch just above his head, getting ready to strike. The contractor moved on before

the snake could react. Forest Blanchard, in an article on the canal activities near the

Shelby County village of Oran, described how local farmers who owned a team of oxen or

horses were paid $1.25 a day to work on the canal. With land prices then at about the same

price per acre, Oran area resident Samuel Penrod amassed almost 600 acres of land by

providing such services.

The canal bisected many roads along the way. Travelers on the roads had to have a way

across the canal. In many cases, this problem was solved with a 'swing' or 'bump' bridge.

This bridge would allow a horse and buggy or wagon to pass over the canal. Canal boats

would approach the bridge and bump the structure, pivoting it out of the way. Some bridges

were more substantial in character.

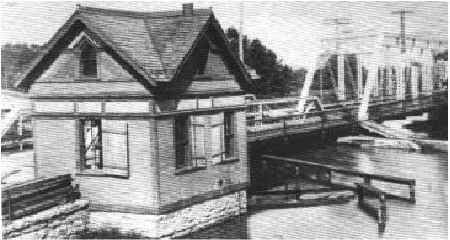

Piqua's steam-operated swing bridge over the canal on Main

Street, ca. 1910. The small building contained the steam engine that operated the

mechanism. |

| Work stoppages were common when the canal work

was at its height in Shelby County, Ohio, and the rest of the nation was in the midst of

an economic depression known as the 'Panic of 1837'. It was eight years before the entire

Miami & Erie Canal was completed, and the county residents could enjoy the full

benefits canal business had to offer. The Sidney Feeder was 14 miles long, beginning at a

dam on the Great Miami River just north of Port Jefferson, and ending at Lock No. 1 in

Lockington. It was built 50 feet wide at the top, and contained no locks. The feeder canal

paralleled the Great Miami River most of the way from Port Jefferson to Sidney. It entered

Sidney from the northeast and moved in a southwesterly direction through the center of

town, passing behind what is now Crescent Avenue.

'Canal' segment written in

December, 1998 by Rich Wallace

[ Back to Canal Index ] |

|